The Richmond Sixteen – Robert Lown of Ely - Conscientious Objector

In January 1916 the Military Service Act 1916 introduced conscription to Great Britain and single men aged between eighteen and forty-one were liable to call-up for war service in the Army. There were exemptions for ministers of religion, those engaged in "work of national importance", men with dependants such as widowers with young children, and men who were disabled or in poor health. There was also provision for those with conscientious objections to fighting, ("COs"): men could object on religious or moral grounds, but even if they were accepted as genuine conscientious objectors by the Tribunals set up under the Act, they could still be conscripted into the Army for non-combatant duties. One man who proclaimed himself to be a CO was Robert Armstrong Lown, bookseller, of Ely. Robert was then thirty- four years old (born 21st June 1881), and the older brother of Sydney Lown who was to be killed in action in 1918. He was living in Mill View House, West End, Ely. Robert’s stance was a political one; he was a member of the Independent Labour Party and part of Ely’s No-Conscription Fellowship.

Thousands of men claiming to be conscientious objectors were questioned by the Tribunals, but very few were actually exempted from all kinds of war service. The vast majority were ordered to fight or to join the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), which were especially created exclusively for COs. Thus although it was accepted they had genuine moral or religious objections to fighting, these men were still under military orders in the NCC and supporting the war in a non-fighting role. A relatively small number refused these non-combatant duties and were labelled "absolutists".

When it was the turn of the group in which Richard had been listed to report to the military authorities for placement in a regiment he should have responded by either enlisting or appealing to the Ely Urban Military Tribunal to request exemption from service - he did neither. He was consequently summoned on 11th May 1916 at Ely Petty Sessions and arrested at his home by PC Green, to whom he reportedly said "I have been expecting you for some time". His case was adjourned for a week to allow documentary evidence to be assembled to demonstrate that he was an Army Reservist - but when he was called to the Petty Sessions of May 18th the charges were withdrawn as he was said to have joined up. The newspaper later reported that at neither of these appearances did he proclaim himself to be a conscientious objector. Instead of enlisting, however, Robert then appealed to the Military Tribunal for exemption.

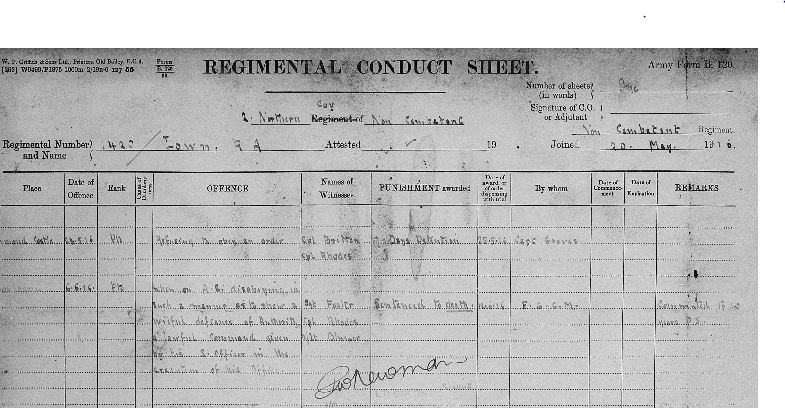

Robert Lown was accepted as a genuine CO on political grounds by the Tribunal but ordered to report to the NCC. He was taken to join the 2nd Northern Company of the Non-Combatant Corps (Service Number 1420), which was stationed at Richmond Castle, in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Here he refused to wear uniform or undertake any duties at all, and so ended up locked in the cells pending court-martial for disobeying military orders. In total, sixteen COs ended up in the cells in Richmond Castle. As a punishment for their resistance the men were put on a bread and water diet; eight were put in detention cells while seven were crammed in the Guardroom. Some were later transferred to the dungeon under the Keep. Other similar acts of disobedience by forcibly enlisted COs had taken place over the past two months at military barracks and camps around the country and the COs would have known that these acts of defiance had resulted in courts-martial and sentences of imprisonment. Robert was prepared to stand on his principles and accept this probability of imprisonment for the duration of the War.

The military hierarchy (perhaps Lord Kitchener himself who had introduced conscription in the first place) determined that four random groups of the resisting COs, forty-two absolutists in all, should be sent to the Western Front, where they could be made an example of; if they were court-martialled abroad for refusing to obey orders they could then face the death penalty. Accordingly the groups imprisoned at Harwich, Seaford, Abergele and Richmond were selected - including Robert Lown. When the time came to be taken abroad, on 29th May 1916, the Richmond men did not go willingly; it is said they offered resistance by clinging to tables, chairs or doorframes and, not for the first time, got some rough handling from their guards.

While the Richmond Sixteen were on a train being escorted south, one of them addressed a desperate letter to a fellow-Quaker, Arnold Rowntree, the Member of Parliament for York, writing about their predicament, and threw it out of the train window. The letter was picked up and quickly reached Rowntree, who immediately took the matter up with Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.

On arrival in France, the men were moved from place to place, spending their time in a variety of guard rooms, sometimes lodged "on parole" in rest camps, and were eventually held with other prisoners in insalubrious conditions near Boulogne. At Boulogne they were told they were "in the presence of the enemy" and that disobeying orders could now result in their being shot as deserters. They were urged to join other COs who had accepted their assigned role in the NCC, in fact they were informed that a previous group of objectors had saved their lives by deciding to obey military orders. The sixteen men were then given twenty-four hours' leave to make up their minds, and they considered their position at leisure, five of them even going swimming! All remained convinced that supporting the war in any way would be morally wrong, and as a group they decided to hold out. However, at this point one man decided to give in and agreed to join the NCC men unloading war supplies from ships at Boulogne docks.

The next day, the other fifteen Richmond men continued to refuse to obey all orders and were returned to the guard room. They were then court martialled at Henriville Camp (Boulogne), found guilty, and on 14th June 1916 were sentenced to be shot at dawn. However, Kitchener had died on 5th June, and this is probably part of the reason the sentence was commuted to ten years hard labour by the Prime Minister, Asquith. On Saturday 24th June the fifteen were, however taken all the way to the place of execution, in front of thousands of troops, before they heard the news of their reprieve.

On their return from France the “Richmond Sixteen”, with the other absolutists, were imprisoned again in labour camps and civil prisons. On 4th July Robert left France for Winchester Prison. On 1st November he was officially transferred to the Army Reserve (Class W) and sent to Warwick. On 28th August 1917 Robert was sent to Dartmoor Prison where he remained until he was officially demobbed on 31st May 1920 – much later than most of the actual combatants.

Although they stayed true to their pacifist principles, the COs’ imprisonment meant that many of them suffered severe long-term psychological effects. After their release many COs found themselves social outcasts unable to get jobs or settle back into the lives and communities they had left behind. How was Robert affected?

Robert Armstrong Lown returned to his birthplace of Smallburgh in Norfolk where he lived with Robert and Gertrude Sandell and became a grocer’s manager (1939). He died on 5th November 1954.

Thousands of men claiming to be conscientious objectors were questioned by the Tribunals, but very few were actually exempted from all kinds of war service. The vast majority were ordered to fight or to join the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), which were especially created exclusively for COs. Thus although it was accepted they had genuine moral or religious objections to fighting, these men were still under military orders in the NCC and supporting the war in a non-fighting role. A relatively small number refused these non-combatant duties and were labelled "absolutists".

When it was the turn of the group in which Richard had been listed to report to the military authorities for placement in a regiment he should have responded by either enlisting or appealing to the Ely Urban Military Tribunal to request exemption from service - he did neither. He was consequently summoned on 11th May 1916 at Ely Petty Sessions and arrested at his home by PC Green, to whom he reportedly said "I have been expecting you for some time". His case was adjourned for a week to allow documentary evidence to be assembled to demonstrate that he was an Army Reservist - but when he was called to the Petty Sessions of May 18th the charges were withdrawn as he was said to have joined up. The newspaper later reported that at neither of these appearances did he proclaim himself to be a conscientious objector. Instead of enlisting, however, Robert then appealed to the Military Tribunal for exemption.

Robert Lown was accepted as a genuine CO on political grounds by the Tribunal but ordered to report to the NCC. He was taken to join the 2nd Northern Company of the Non-Combatant Corps (Service Number 1420), which was stationed at Richmond Castle, in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Here he refused to wear uniform or undertake any duties at all, and so ended up locked in the cells pending court-martial for disobeying military orders. In total, sixteen COs ended up in the cells in Richmond Castle. As a punishment for their resistance the men were put on a bread and water diet; eight were put in detention cells while seven were crammed in the Guardroom. Some were later transferred to the dungeon under the Keep. Other similar acts of disobedience by forcibly enlisted COs had taken place over the past two months at military barracks and camps around the country and the COs would have known that these acts of defiance had resulted in courts-martial and sentences of imprisonment. Robert was prepared to stand on his principles and accept this probability of imprisonment for the duration of the War.

The military hierarchy (perhaps Lord Kitchener himself who had introduced conscription in the first place) determined that four random groups of the resisting COs, forty-two absolutists in all, should be sent to the Western Front, where they could be made an example of; if they were court-martialled abroad for refusing to obey orders they could then face the death penalty. Accordingly the groups imprisoned at Harwich, Seaford, Abergele and Richmond were selected - including Robert Lown. When the time came to be taken abroad, on 29th May 1916, the Richmond men did not go willingly; it is said they offered resistance by clinging to tables, chairs or doorframes and, not for the first time, got some rough handling from their guards.

While the Richmond Sixteen were on a train being escorted south, one of them addressed a desperate letter to a fellow-Quaker, Arnold Rowntree, the Member of Parliament for York, writing about their predicament, and threw it out of the train window. The letter was picked up and quickly reached Rowntree, who immediately took the matter up with Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.

On arrival in France, the men were moved from place to place, spending their time in a variety of guard rooms, sometimes lodged "on parole" in rest camps, and were eventually held with other prisoners in insalubrious conditions near Boulogne. At Boulogne they were told they were "in the presence of the enemy" and that disobeying orders could now result in their being shot as deserters. They were urged to join other COs who had accepted their assigned role in the NCC, in fact they were informed that a previous group of objectors had saved their lives by deciding to obey military orders. The sixteen men were then given twenty-four hours' leave to make up their minds, and they considered their position at leisure, five of them even going swimming! All remained convinced that supporting the war in any way would be morally wrong, and as a group they decided to hold out. However, at this point one man decided to give in and agreed to join the NCC men unloading war supplies from ships at Boulogne docks.

The next day, the other fifteen Richmond men continued to refuse to obey all orders and were returned to the guard room. They were then court martialled at Henriville Camp (Boulogne), found guilty, and on 14th June 1916 were sentenced to be shot at dawn. However, Kitchener had died on 5th June, and this is probably part of the reason the sentence was commuted to ten years hard labour by the Prime Minister, Asquith. On Saturday 24th June the fifteen were, however taken all the way to the place of execution, in front of thousands of troops, before they heard the news of their reprieve.

On their return from France the “Richmond Sixteen”, with the other absolutists, were imprisoned again in labour camps and civil prisons. On 4th July Robert left France for Winchester Prison. On 1st November he was officially transferred to the Army Reserve (Class W) and sent to Warwick. On 28th August 1917 Robert was sent to Dartmoor Prison where he remained until he was officially demobbed on 31st May 1920 – much later than most of the actual combatants.

Although they stayed true to their pacifist principles, the COs’ imprisonment meant that many of them suffered severe long-term psychological effects. After their release many COs found themselves social outcasts unable to get jobs or settle back into the lives and communities they had left behind. How was Robert affected?

Robert Armstrong Lown returned to his birthplace of Smallburgh in Norfolk where he lived with Robert and Gertrude Sandell and became a grocer’s manager (1939). He died on 5th November 1954.