Mothers, Wives and Sisters – The VAD Hospital and the War Work Depot

As husbands, sons, and brothers went to War the women of Ely rallied around to support the War effort and two of the particular ways they did this was through the VAD Hospital and through the War Work Depot, both, at one stage, on Barton Square.

The VAD Hospital

As early as 1909 the War Office had a scheme for recruiting volunteers who could support the Territorial Forces Medical Service in the event of a war. The scheme created voluntary aid detachments (VADs) and members were trained in first aid and nursing. At the outbreak of the First World War, the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem combined to form the Joint War Committee The Red Cross secured buildings, equipment and staff, and was able to set up temporary hospitals as soon as wounded men began to arrive from abroad. The buildings used varied widely, ranging from town halls and schools to large and small private houses, both in the country and in cities, and early on there was a belief that the schools in the Isle of Ely would be commandeered for this purpose. This belief had to be officially repudiated in the Ely Standard.

Over 3,000 auxiliary hospitals were set up across Britain - these were administered by Red Cross county directors, and women in the local neighbourhood volunteered on a part-time basis. The hospitals would also have a few paid roles, such as cooks and night orderlies. These hospitals were usually served by local doctors (also volunteers). This meant that the patients at VAD hospitals were necessarily those who were less seriously wounded and were convalescing. Such hospitals were often less crowded and more homely than the big military hospitals. In Ely the old Militia Hospital in Silver Street, which had become the headquarters of the Women’s Conservative Association, was turned again to its former use as a hospital in October of 1915 and managed by Ely VAD.

The roll call of the first nursing team was: Commandant Mrs Catherine Punchard (wife of the vicar of St Mary’s); Assistant Commandant Mrs Katherine Bidwell; Quartermaster Mrs Christina Fyfe; Assistant Quartermaster Mrs Helen McKelvie; Matron Mrs Louisa Greenstreet (wife of the rector of Little Downham); and Nurses Misses Frances Allen, Dorothy Adeline Luddington Archer (sister of Major Archer), H Archer, Vera Bowles, Bowsher, Fanny Collins, Dorothy Evans, Constance Fox, Emily Sharman Franey, Dorothy Kirkpatrick (daughter of the Dean of Ely Cathedral), Lincoln, F Lincoln, Cicely Mander (daughter of the chief constable), Alice Puxley, Hilda Wordingham, Mrs Ethel Saunders and Mrs Annie Harris (wife of Dr Harris). Others who later became VADs included: Hilda Fennings; A Haylock; Alice Toombs; Constance Fox and the Misses Marshall, Coy and Comins. Thirty-one members of Cambridgeshire V.A.D. in total were to work at the Ely hospital over the period of the war. some for its entire duration. The staff also included a trained nurse, known always as "Nurse Clarke"; she was one of the sisters of fatality Dick Clarke. (Mary Clarke was later to become Ely's Red Cross Commandant, working out of Ely Dispensary.) The medical officer for the hospital was local doctor Henley F Curl.

In addition, many local volunteers took regular turns at the hospital working as orderlies - one such was army pensioner William Sanderson, then in his late 50s, who had served with the Royal Engineers and then retired home to Ely in 1900. William worked in the hospital for most of the war, then died soon afterwards in February 1920. A young teenage volunteer, Archie Denstone, spent most of the War as a messenger for the hospital, and a determined team of ladies took on the hospital kitchens with Mrs Louisa Barwell, Mrs Louisa Foster, Mrs Langhorne, Mrs Jones, Mrs A Seymour and Mrs W Seymour being named as having served for the entire three years and seven months the hospital was open. Mr Alexander Cass, the local cycle and motor agent, also took on the role of taxi, using his personal car to ferry soldiers to and from the station and also taking them out for countryside drives.

Very soon the first 24 of the wounded arrived at Ely. They were known by the citizens as the “Blue Boys” because of their blue army suits, hats and overcoats and became a familiar sight around the city. The Ely Standard commented: “Despite their wounds – it is apparent that some of the invalids will be unfit for any further service – the men appear bright and cheerful.” The hospital was also open to visitors who wished to support the soldiers any day except Friday from 3.00- 4.30 p.m. The people of Ely as a whole took on the support of their hospital; every week the Ely Standard included a list of thanks to donors for the gifts given to the hospital which included food, furniture and various comforts such as cigarettes. They were also given regular treats such as concerts, parties, and other entertainments, or drives in the country.

The hospital moved into larger premises in Ely Theological College in August 1916 and was "extended to 20 beds". The Silver Street School's pupils were keen supporters of the hospital at this time, with the boys making the extra lockers and boards required for the extra patients, while the girls set to work repairing the socks which had been sent from the military store and were so badly made as to be unusable. The Theological College Chaplain stayed in post to become the hospital's chaplain.

After this the hospital seems to have an average of about 30 patients at a time, although in December 1917 apparently a large number of the beds were vacant and the majority of wounded needed no medical attention.

Some of the wounded men at the hospital became popular Ely characters in their own right. On 4th October 1918 a newspaper article announced that one of these men, Sergeant Peter “Jock” Maclaren “who, during his stay in the city, made a host of friends” had died of wounds on 3rd September. (This was Peter Lyon McLaren of the Black Watch who was in the hospital late in 1915.) A rather happier notice appeared on 3rd January 1919, with the news that VAD Miss Puxley had married an Australian officer, John Francis. Alice Puxley worked at one of the Ely stores and had given every Tuesday afternoon and Sunday to hospital work throughout the War.

Other recovering soldiers' behaviour caused issues in Ely - especially when they went out on the town and got drunk! By 1916 posters were up around the city reminding the citizens that it was an offence to buy beer for wounded soldiers. In September 1916 sixteen year old Thomas William Gotobed was summoned at Ely Petty Sessions - he had been accosted in the park after dark by some of the men from the hospital who had persuaded him to go and buy a total of six bottles of beer for them. Thomas was lucky, he pleaded that he knew nothing about the alcohol ban and was fined only £1 ( it could have been as much as £100!). Apparently the guilty soldiers were moved on to another hospital.

The hospital was not immune from the influenza pandemic as it swept through the area; because Ely normally looked after less serious cases the staff were not used to losing their patients. On 17th November 1918 twenty-two years old Private Albert Harper of the Monmouthshire Regiment died in Ely of pneumonia. He had been visited by family members when he was recuperating at Ely, and they requested he be sent home to Ebbw Vale for burial.

When the War ended the Commandant found that many of the night orderlies immediately gave up their posts, some even moving away. In January of 1919 she had to appeal through the local newspaper for more support while the hospital remained open. It is also noticeable that the gifts of food and comforts which had been donated to the hospital throughout the War by the citizens of Ely virtually dried up. At this stage the hospital still had 24 long term patients who eventually had to be taken to Cambridge so that the hospital could be decommissioned.

By the time the Hospital closed in May 1919 it had treated 1,117 patients. It had already been agreed by the local council that the hospital's outpatients service would still be needed for the foreseeable future for treating discharged soldiers and so this was moved to the Dispensary on St Mary's Street. Various pieces of equipment such as bath chairs were retained for use by local disabled soldiers, but also with the hope that Ely's War Memorial might take the form of a cottage hospital and the equipment could be used again here (this did not happen).

Although the hospital had closed the members of the VAD continued to be active and in February 1920 they were engaged in raising funds for the reconstruction of homes in France. The names of those organising the ongoing work were the Mrs Helen McKelvie, Winifred Comins, Louisa Cobb with Miss Elizabeth Titterton and Miss Peck..

The VAD Hospital even brought about some marriages; in April 1921 Constance Mabel Fox married Thomas Lloyd Griffiths of the Welsh Yeomanry, one of her former patients.

In August of 1919 Miss L.E. Anson, the matron of Ely Auxiliary Hospital, was awarded the Royal Red Cross (Second Class) "in recognition of valuable nursing services rendered in connection with the war".

Volunteer Nurses and "Blue Boys" at the original Silver Street Hospital The Theological College became the new hospital in 1916

The VAD Hospital

As early as 1909 the War Office had a scheme for recruiting volunteers who could support the Territorial Forces Medical Service in the event of a war. The scheme created voluntary aid detachments (VADs) and members were trained in first aid and nursing. At the outbreak of the First World War, the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem combined to form the Joint War Committee The Red Cross secured buildings, equipment and staff, and was able to set up temporary hospitals as soon as wounded men began to arrive from abroad. The buildings used varied widely, ranging from town halls and schools to large and small private houses, both in the country and in cities, and early on there was a belief that the schools in the Isle of Ely would be commandeered for this purpose. This belief had to be officially repudiated in the Ely Standard.

Over 3,000 auxiliary hospitals were set up across Britain - these were administered by Red Cross county directors, and women in the local neighbourhood volunteered on a part-time basis. The hospitals would also have a few paid roles, such as cooks and night orderlies. These hospitals were usually served by local doctors (also volunteers). This meant that the patients at VAD hospitals were necessarily those who were less seriously wounded and were convalescing. Such hospitals were often less crowded and more homely than the big military hospitals. In Ely the old Militia Hospital in Silver Street, which had become the headquarters of the Women’s Conservative Association, was turned again to its former use as a hospital in October of 1915 and managed by Ely VAD.

The roll call of the first nursing team was: Commandant Mrs Catherine Punchard (wife of the vicar of St Mary’s); Assistant Commandant Mrs Katherine Bidwell; Quartermaster Mrs Christina Fyfe; Assistant Quartermaster Mrs Helen McKelvie; Matron Mrs Louisa Greenstreet (wife of the rector of Little Downham); and Nurses Misses Frances Allen, Dorothy Adeline Luddington Archer (sister of Major Archer), H Archer, Vera Bowles, Bowsher, Fanny Collins, Dorothy Evans, Constance Fox, Emily Sharman Franey, Dorothy Kirkpatrick (daughter of the Dean of Ely Cathedral), Lincoln, F Lincoln, Cicely Mander (daughter of the chief constable), Alice Puxley, Hilda Wordingham, Mrs Ethel Saunders and Mrs Annie Harris (wife of Dr Harris). Others who later became VADs included: Hilda Fennings; A Haylock; Alice Toombs; Constance Fox and the Misses Marshall, Coy and Comins. Thirty-one members of Cambridgeshire V.A.D. in total were to work at the Ely hospital over the period of the war. some for its entire duration. The staff also included a trained nurse, known always as "Nurse Clarke"; she was one of the sisters of fatality Dick Clarke. (Mary Clarke was later to become Ely's Red Cross Commandant, working out of Ely Dispensary.) The medical officer for the hospital was local doctor Henley F Curl.

In addition, many local volunteers took regular turns at the hospital working as orderlies - one such was army pensioner William Sanderson, then in his late 50s, who had served with the Royal Engineers and then retired home to Ely in 1900. William worked in the hospital for most of the war, then died soon afterwards in February 1920. A young teenage volunteer, Archie Denstone, spent most of the War as a messenger for the hospital, and a determined team of ladies took on the hospital kitchens with Mrs Louisa Barwell, Mrs Louisa Foster, Mrs Langhorne, Mrs Jones, Mrs A Seymour and Mrs W Seymour being named as having served for the entire three years and seven months the hospital was open. Mr Alexander Cass, the local cycle and motor agent, also took on the role of taxi, using his personal car to ferry soldiers to and from the station and also taking them out for countryside drives.

Very soon the first 24 of the wounded arrived at Ely. They were known by the citizens as the “Blue Boys” because of their blue army suits, hats and overcoats and became a familiar sight around the city. The Ely Standard commented: “Despite their wounds – it is apparent that some of the invalids will be unfit for any further service – the men appear bright and cheerful.” The hospital was also open to visitors who wished to support the soldiers any day except Friday from 3.00- 4.30 p.m. The people of Ely as a whole took on the support of their hospital; every week the Ely Standard included a list of thanks to donors for the gifts given to the hospital which included food, furniture and various comforts such as cigarettes. They were also given regular treats such as concerts, parties, and other entertainments, or drives in the country.

The hospital moved into larger premises in Ely Theological College in August 1916 and was "extended to 20 beds". The Silver Street School's pupils were keen supporters of the hospital at this time, with the boys making the extra lockers and boards required for the extra patients, while the girls set to work repairing the socks which had been sent from the military store and were so badly made as to be unusable. The Theological College Chaplain stayed in post to become the hospital's chaplain.

After this the hospital seems to have an average of about 30 patients at a time, although in December 1917 apparently a large number of the beds were vacant and the majority of wounded needed no medical attention.

Some of the wounded men at the hospital became popular Ely characters in their own right. On 4th October 1918 a newspaper article announced that one of these men, Sergeant Peter “Jock” Maclaren “who, during his stay in the city, made a host of friends” had died of wounds on 3rd September. (This was Peter Lyon McLaren of the Black Watch who was in the hospital late in 1915.) A rather happier notice appeared on 3rd January 1919, with the news that VAD Miss Puxley had married an Australian officer, John Francis. Alice Puxley worked at one of the Ely stores and had given every Tuesday afternoon and Sunday to hospital work throughout the War.

Other recovering soldiers' behaviour caused issues in Ely - especially when they went out on the town and got drunk! By 1916 posters were up around the city reminding the citizens that it was an offence to buy beer for wounded soldiers. In September 1916 sixteen year old Thomas William Gotobed was summoned at Ely Petty Sessions - he had been accosted in the park after dark by some of the men from the hospital who had persuaded him to go and buy a total of six bottles of beer for them. Thomas was lucky, he pleaded that he knew nothing about the alcohol ban and was fined only £1 ( it could have been as much as £100!). Apparently the guilty soldiers were moved on to another hospital.

The hospital was not immune from the influenza pandemic as it swept through the area; because Ely normally looked after less serious cases the staff were not used to losing their patients. On 17th November 1918 twenty-two years old Private Albert Harper of the Monmouthshire Regiment died in Ely of pneumonia. He had been visited by family members when he was recuperating at Ely, and they requested he be sent home to Ebbw Vale for burial.

When the War ended the Commandant found that many of the night orderlies immediately gave up their posts, some even moving away. In January of 1919 she had to appeal through the local newspaper for more support while the hospital remained open. It is also noticeable that the gifts of food and comforts which had been donated to the hospital throughout the War by the citizens of Ely virtually dried up. At this stage the hospital still had 24 long term patients who eventually had to be taken to Cambridge so that the hospital could be decommissioned.

By the time the Hospital closed in May 1919 it had treated 1,117 patients. It had already been agreed by the local council that the hospital's outpatients service would still be needed for the foreseeable future for treating discharged soldiers and so this was moved to the Dispensary on St Mary's Street. Various pieces of equipment such as bath chairs were retained for use by local disabled soldiers, but also with the hope that Ely's War Memorial might take the form of a cottage hospital and the equipment could be used again here (this did not happen).

Although the hospital had closed the members of the VAD continued to be active and in February 1920 they were engaged in raising funds for the reconstruction of homes in France. The names of those organising the ongoing work were the Mrs Helen McKelvie, Winifred Comins, Louisa Cobb with Miss Elizabeth Titterton and Miss Peck..

The VAD Hospital even brought about some marriages; in April 1921 Constance Mabel Fox married Thomas Lloyd Griffiths of the Welsh Yeomanry, one of her former patients.

In August of 1919 Miss L.E. Anson, the matron of Ely Auxiliary Hospital, was awarded the Royal Red Cross (Second Class) "in recognition of valuable nursing services rendered in connection with the war".

Volunteer Nurses and "Blue Boys" at the original Silver Street Hospital The Theological College became the new hospital in 1916

The War Work Supplies Depot

The War Works Supplies Depot was set up in a cottage belonging to Theological College Trust (which was donated rent free) and opened on 29th October 1915. (This appears to be the cottage in the grounds of the College on Barton Square, currently occupied by the Warden of Bishop Woodford (Retreat) House.) The depot was opened by the Bishop and headed by his wife, Mrs Elizabeth Armitage Chase. The rooms of the cottage were converted to become an office and receiving room, and machine room on the ground floor, with two hospital rooms upstairs along with two rooms for making requisites and a room where knitting was given out to be done at home.

The team running the depot were: Chair Mrs Elizabeth Chase ; Secretary Mrs Florence Harlock (of the brewery family); with Mrs Barber, Mrs Leila Luddington (wife of the Territorial commander), Marie Mander (wife of the chief constable), Jessie Beckett (wife of Dr Beckett), Louisa Pledger (of Pledgers drapers), Mildred Campion (wife of a cathedral canon), Jane Peck (of Pecks ironmongers), Agnes Curl (wife of Dr Curl), Rhoda Ivatt, and Misses Bidwell, and Marguerite Archer. The depot was affiliated to the Central Council of War Depots. The depot made supplies, especially knitted and flannel garments, for hospitals abroad – the first supplies are known to have been sent out to Serbia.

The depot later moved into a larger space in the Gallery of the Bishop’s Palace, one presumes this decision was made by Mrs Chase herself, as this was her own home.

The depot team asked the population of Ely for weekly or monthly donations of 1d or more to support their work, and there were constant appeals in the newspapers for supplies such as linen for bandage making. The depot was open from 10 a.m. -1 p.m. and 2-5 p.m. daily for work, and for collecting materials to work at home. Women from throughout the local area contributed to the Ely depot; a Sub-depot was set up early in 1916 in Sutton. This was followed by Sub-depots and working parties at Little Downham, Stretham, Wentworth, Wilburton, Longstanton and Pampisford.

Sufficient work was done to send a large parcel of supplies to a casualty clearing station once a fortnight. In all, Ely and its sub-depots supplied 27 hospitals and casualty clearing stations in France, Belgium, Lancashire and Newcastle. This was calculated as 7,548 articles dispatched to British troops, 70,143 items sent to British sick in England, and 10,028 articles dispatched to British allies. The total of the subscriptions collected for the depot’s work was recorded as £1,211 14 6d, out of which only £123 1 2d was used for the running of the depot itself over three years.

The hospital room where the supplies were made closed on 8th February 1919, and the whole operation closed down the following month once the last supplies had been dispersed. The committee had been given a grant of £300 just a couple of months before the end of the war and were able to return two-thirds of this to the War Fund Society.

Mrs Chase kept the wartime sewing committee going as the Society of Ely Workers and in 1921 they were still using up leftover materials from the war supplies depot making garments for children, which are sent to London Hospitals and Save the Children’s Fund, as well as supplies for medical missions and the Mission to Seamen. 138 garments were made in 1920.

The War Works Supplies Depot was set up in a cottage belonging to Theological College Trust (which was donated rent free) and opened on 29th October 1915. (This appears to be the cottage in the grounds of the College on Barton Square, currently occupied by the Warden of Bishop Woodford (Retreat) House.) The depot was opened by the Bishop and headed by his wife, Mrs Elizabeth Armitage Chase. The rooms of the cottage were converted to become an office and receiving room, and machine room on the ground floor, with two hospital rooms upstairs along with two rooms for making requisites and a room where knitting was given out to be done at home.

The team running the depot were: Chair Mrs Elizabeth Chase ; Secretary Mrs Florence Harlock (of the brewery family); with Mrs Barber, Mrs Leila Luddington (wife of the Territorial commander), Marie Mander (wife of the chief constable), Jessie Beckett (wife of Dr Beckett), Louisa Pledger (of Pledgers drapers), Mildred Campion (wife of a cathedral canon), Jane Peck (of Pecks ironmongers), Agnes Curl (wife of Dr Curl), Rhoda Ivatt, and Misses Bidwell, and Marguerite Archer. The depot was affiliated to the Central Council of War Depots. The depot made supplies, especially knitted and flannel garments, for hospitals abroad – the first supplies are known to have been sent out to Serbia.

The depot later moved into a larger space in the Gallery of the Bishop’s Palace, one presumes this decision was made by Mrs Chase herself, as this was her own home.

The depot team asked the population of Ely for weekly or monthly donations of 1d or more to support their work, and there were constant appeals in the newspapers for supplies such as linen for bandage making. The depot was open from 10 a.m. -1 p.m. and 2-5 p.m. daily for work, and for collecting materials to work at home. Women from throughout the local area contributed to the Ely depot; a Sub-depot was set up early in 1916 in Sutton. This was followed by Sub-depots and working parties at Little Downham, Stretham, Wentworth, Wilburton, Longstanton and Pampisford.

Sufficient work was done to send a large parcel of supplies to a casualty clearing station once a fortnight. In all, Ely and its sub-depots supplied 27 hospitals and casualty clearing stations in France, Belgium, Lancashire and Newcastle. This was calculated as 7,548 articles dispatched to British troops, 70,143 items sent to British sick in England, and 10,028 articles dispatched to British allies. The total of the subscriptions collected for the depot’s work was recorded as £1,211 14 6d, out of which only £123 1 2d was used for the running of the depot itself over three years.

The hospital room where the supplies were made closed on 8th February 1919, and the whole operation closed down the following month once the last supplies had been dispersed. The committee had been given a grant of £300 just a couple of months before the end of the war and were able to return two-thirds of this to the War Fund Society.

Mrs Chase kept the wartime sewing committee going as the Society of Ely Workers and in 1921 they were still using up leftover materials from the war supplies depot making garments for children, which are sent to London Hospitals and Save the Children’s Fund, as well as supplies for medical missions and the Mission to Seamen. 138 garments were made in 1920.

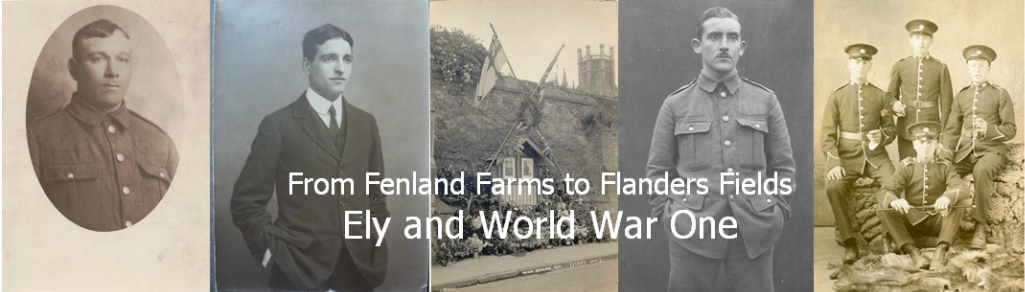

A very dark newspaper photograph shows the staff of the VAD Hospital in Silver Street and the wounded men resident at Christmas time in 1915. Those present are named, but, unfortunately not in the order in which they appear in the photograph: "The group comprises the following:- Staff- Commandant, Mrs Punchard; Matron, Mrs Greenstreet; Quartermaster, Mrs Fyfe; Assistant Commandant, Mrs Bidwell; Assistant Quartermaster, Mrs McKeene; Masseuses, Nurse Clarke and Miss E M Suffling; Nurses, Mrs Saunders, Mrs Harris, Miss E Franey, the Misses Kirkpatrick, Evans, Archer, H Archer, C Mander, Bowles, Puxley, Wordingham, and Fox; Orderly, Barker; Soldiers - Sergeant McLaren, Corporal Bladwell, Lance-Corporal King, Gunner Jefferies, Sapper Croyden, Drummers Hawkins and Wagstaff, Driver Bootman, Privates Price Griffiths, Whitfield, Taylor, Sparkes and Tyler." (The nurses have red crosses on their uniforms, those without a cross will be VADS.)