Smoking and the Front

It is well known that the dangers of smoking were not realised a century ago and, in fact, that cigarettes and tobacco were well regarded and popular comforts for the troops, giving some relief in cold and wet of the Flanders mud.

Tracking the smoking phenomenon through the pages of the local newspapers, shows that it played a part from the very beginning of the war, with some of the first local recruiting drives being advertised as “smoking concerts” or “smokers”, in other words, sessions where men would smoke and listen to presentations from the recruiters.

At Christmas 1914, Princess Mary, the daughter of King George and Queen Mary, gave her name to a public fund for tens of thousands of tins containing home comforts to be sent to servicemen on the Western Front, on the high seas, and in the new air service. She had originally intended to pay for all the tins herself, but the numbers involved were too high. In October 1914 she appealed to the nation:

"I want you now to help me to send a Christmas present from the whole of the nation to every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front. I am sure that we should all be happier to feel that we had helped to send our little token of love and sympathy on Christmas morning, something that would be useful and of permanent value, and the making of which may be the means of providing employment in trades adversely affected by the war. Could there be anything more likely to hearten them in their struggle than a present received straight from home on Christmas Day? Please will you help me?"

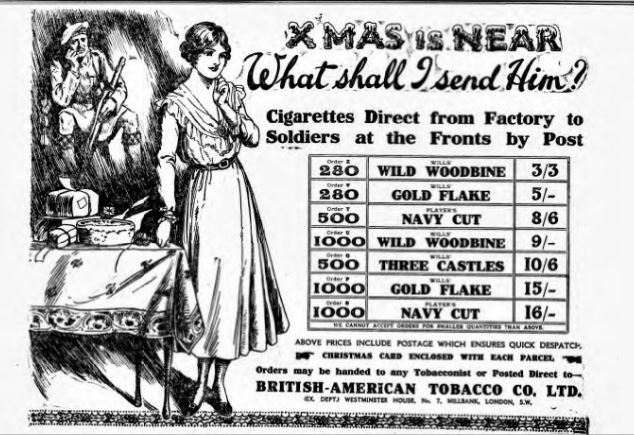

It was intended that the recipients of Princess Mary’s gift would receive an embossed brass box, one ounce of pipe tobacco, twenty cigarettes, a pipe, a tinder lighter, Christmas card and photograph, while non-smokers should receive the brass box, a packet of acid tablets, a khaki writing case containing pencil, paper and envelopes together with the Christmas card and photograph of the Princess. The system did not always work, as Reg Edwards of Prickwillow, a non-smoker, discovered when he received one of the tobacco filled tins.

Those already injured were not forgotten as the Christmas Day newspaper reports: “Twelve hundred boxes containing cigarettes, or tobacco and pipe, or chocolate, will be distributed amongst the man at the 1st Eastern General Hospital at Cambridge on Boxing Day. Should there be less than that number at the Hospital it is hoped that it may be possible to distribute the remainder amongst the patients in the various Red Cross Auxiliary Hospitals in the Borough and County.”

Adverts and articles in the newspapers such as the one following from 22nd January 1915 played on the consciences of Ely readers:

“Ever since our army landed in France the cry from the trenches has been “Send us something to smoke” and it is our solemn duty to answer that cry. Just picture to yourselves the everyday conditions of trench life. The nerve shattering crash of the heavy artillery, and the death dealing shells screaming overhead. In the midst of this inferno our brave lads stand up to their waists in mud and water, and return shot for shot with the Kaiser’s hordes, not knowing who will be the next one to be struck down. Do our heroic Tommies complain? Never! All they say is, “Please send us something to smoke.” To us at home it seems a paltry thing to ask in return for their risking their lives for our country. But for Tommy it is the very opposite of paltry. In spite of the tremendous efforts that have been made, and are being made, to send as much smoking material as possible to the front, a soldier writing home from the trenches says he paid 6d to a comrade for a half-smoked cigarette. Just imagine the joy of that soldier if at the critical moment that he was enviously eyeing his neighbour’s cigarette he had received a week’s supply of smoking material from you. How he would have blessed and thanked you. This little story of the soldier, the half cigarette, and the sixpence, only proves that the value of your sixpence increases one hundred fold when it reaches the trenches in the form of “smokes”. Everyone will remember the saying of Mr Rudyard Kipling’s immortal Malvaney “A smoke is meat an’ drink to me.” And so it is. We earnestly appeal to you to send us just as many sixpences as you can. A large amount of smoking material has already gone to the front but out there tobacco goes a s fast as bullets. So you see, much more money is needed if our brave soldiers are to be kept happy and well provided with the only comfort they ask for, just as long as the war lasts. A postcard addressed to you, is enclosed with every 6d parcel of happiness – your subscription sends to the front. Thus the delighted soldiers who receive your gifts will, if possible, write and thank you for your kindness, because Tommy Atkins is as grateful as he is brave. Why not send us a subscription now, and besides being assured that every 6d you send will make a soldier happy, you will be fortunate enough to receive acknowledgements from the front written in the happy humorous strain that speaks so well for the morale of the splendid and wonderful British Army.”

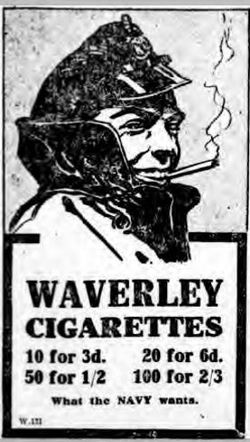

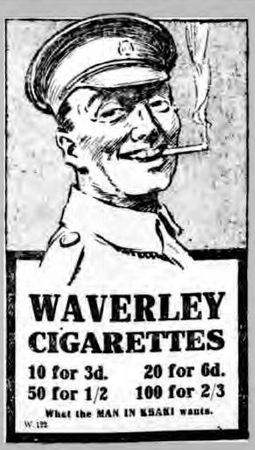

Cigarettes had proved to be important for keeping soldiers occupied during the long stretches of relative quiet and boredom at the Front. They created a sense of camaraderie when shared out among friends, and were even credited with keeping the men away from hard liquor and loose women! Even associations like the YMCA and the Red Cross, which prior to war had been opposed in principle to smoking, ended up collecting vast quantities of cigarettes for the boys, and chaplains such as the famous “Woodbine Willy” gave them out regularly.

Surprisingly the main danger of smoking in the trenches appears to have been not cancer but matches – as lighting matches drew the attention of snipers to men’s positions in the line. This is said to be the origin of the superstition about not lighting three cigarettes from the same match.

The Ely public responded well to requests for cigarettes, sending smokes to their own menfolk, and also responding to general appeals. Often special fundraising drives would figure in the newspapers e.g:

- In November of 1914 the political clubs of the City held a whist drive at the Corn Exchange and raised £3 17s 6d for the members of H Company of the local Territorials who had volunteered for the Front – the money would all be spent on cigarettes and tobacco.

- On Empire Day (24th May) 1915 children throughout the country were encouraged to give their pennies to buy “tobacco, cigarettes and comforts” for the troops. Over three million pennies were subscribed by children throughout the country which paid for 250,000 parcels.

- Samuel Mc Gee, the landlord of the Anchor Inn at Stuntney, raised £1 19s at Christmas 1915 which was spent on tobacco and cigarettes for the fifteen Stuntney men then serving at the Front, including his own half-brothers.

Interestingly, after the War was over Ely’s Literary and Social Guild met at the Countess of Huntingdon Church to debate the question “Is smoking injurious?” “The conclusion arrived at was that smoking is very injurious to all persons under twenty-one years of age, but that after that age smoking is not injurious if engaged in with discretion and moderation.” In fact after the War, the habit of cigarette smoking among all layers of society persisted, quietly but relentlessly, causing premature death amongst the men who survived the fighting but had learned to smoke in the trenches.